Wayne Dyer's last

book (written with Dee Garnes) “Memories of Heaven:Children's Astounding Recollections of the Time before They Came to Earth,” has so much behind it that I

felt overwhelmed by the time I finished reading it this morning.

The authors

explicitly built it around Wordsworth's Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood,

collecting thousands of anecdotes via their Facebook appeal for

accounts of young (mostly under five) children's memories and visions

of heaven. Dyer and Garnes then made a selection of those accounts,

wrote them up and present them in this astonishing book.

We are all pretty

much familiar with the main points of such accounts - the heavens of

light and love, loved ones who have gone on, angels, choosing one's parents-to-be, etc. – and it would be easy to say as many do, “OK, we've heard this all

before, there's no proof, it's all wishful thinking or fraud, it's

all so simplistic and naive and childlike and dangerously

unrealistic.”

I think it's

as equally dishonest just to dismiss these accounts as it is to believe them uncritically. These children's reports may well be true and the

materialistic scientist's view untrue.

The “a-ha,” the

“click,” the “eureka,” that sense of opening and solution and

release that comes with discovery, seems to be part of the scientist's

experience as well as the non-scientist's experience. It's certainly one of the

acid tests of when you've finally discerned what a

dream is trying to tell you.

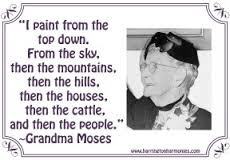

Dyer and Garnes like

good quotes, from poets as well as scientists, and here are two of

them from the book with which you may feel that “click:”

p.195, Albert

Einstein:

“If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy

tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy

tales.”

p.198, William Blake:

Said 'Little

creature, form'd of joy and mirth

Go, love without

the help of anything on Earth.”